Stata training

This “Stata guide” is intended to be a handy resource for you, and you can use it the way you want. It is divided in topic but it is not consequential, meaning you can jump from one chapter to another without any problems.

If you already have a knowledge of what Stata is, you can definitely skip the Stata basic part. I will try to cover from the very basic to the very advanced (as far as I know), but if you think I took something for granted, or something is not well explained shoot me a message at gaiagaudenzi9@gmail.com

Stata Basics

What is Stata?

Nothing else than a statistic software to analyze your data! It is widely used (at least in Economics) and it is very simple to use. You can browse through this training to have a sense of what you can do with it and get used to the language and terminology. Luckily enough, Stata has excellent official resources to learn it and great online support. If you have a question on how to do something, you can look for an answer (if it’s there already) or ask your question on the forum Statalist.

Commands

Stata works with commands. Every line of code you type on Stata corresponds to a command. So with every line, you are asking Stata to perform a different action. This is an example of two lines of command in Stata:

1. use "/Users/gaiagaudenzi/Documents/Stata/dataset.dta"

2. browse

“translated” in plain English, these two lines of code correspond to:

- Open the dataset named “dataset.dta” that is on my laptop, specifically in the directory “/Users/gaiagaudenzi/Documents/Stata/”

- Browse through the variables that are inside this dataset

There are of course many many commands, depending on the operations you want to perform and on which variable. If you are not sure about which command you want to use, or how a command is supposed to be used, Stata will always help you. You just have to type

help

followed by the name of the command (Fun fact: help is iteslf a command, that helps you understand other commands). Stata will open the documentation and show you some examples on how to use that command. Througout this training, I will make extensive use of the data documentation, so that you can get familiar with it and become more and more independent.

Structure of a command

To let you know how the help command works, and what is the basic structure of a command as you see it on the Stata documentation, I take the code summarize as an example. It is a code that calculates for you the number of observations, the mean, the standard deviation, the minimum and the maximum of a variable. By typing help summarize we get the syntax of this code:

summarize [varlist] [if] [in] [weight] [, options]

Let’s start talking about how you can actually load datasets on Stata. The extension stata uses for its file is .dta, so the name of a dataset in Stata format will look like this: dataset.dta. However, you can import a wide variety of files with different formats into Stata (Excel, csv etc.)

Directories

How can you locate on your laptop the files you will load into Stata? With the directory of the file itself! For every file you import/load in Stata you have to specify the directory, to tell Stata where exactly it has to find the file. So, to load a .dta file into Stata, you will use the following syntax:

use "yourdirectory/dataset.dta"

Where “yourdirectory” is the directory where the file is. For example, in the box below, I show the directory of the file example.dta contained on my computer in the directory “/Users/gaiagaudenzi/Documents/Stata”

use "/Users/gaiagaudenzi/Documents/Stata/dataset.dta"

This will open the file dataset.dta on Stata.

To know in which directory you are at the moment, type on the Command prompt:

pwd

It will return the directory Stata is in. In my case now it is:

"/Users/gaiagaudenzi/Documents/Stata/dataset.dta"

To change directory (in this example I change from “/Users/gaiagaudenzi/Documents/Stata” to “/Users/gaiagaudenzi/Documents/Datasets”)

cd “/Users/gaiagaudenzi/Documents/Datasets”

To create directories (this will create folders into your laptop! In this example I create the folder “NewDirectory”)

mkdir “/Users/gaiagaudenzi/Documents/NewDirectory”

Importing data from Stata and from external sources (.xlsx, .csv, etc.)

We have already seen that to load a dataset into Stata that is already in .dta format, the command is use followed by the directory and the name of the file. What if we want to import an Excel file?

import excel using “yourdirectory/SampleExcelFile.xlsx”, clear

N.B. Stata only allows to open one variable at a time. This means that you will always have to specify the option

clearafter the comma as in the example above. Otherwise Stata will give you an error of this type:

no; data in memory will be lost

Setup

How to organize your workflow

Use dofiles!

When using Stata for research, one of your first concerns should be how to make sure your work is transparent and reproducible, and how to make sure that, if you look at a clean dataset 5 years after, you are able to trace back any modification you make to the raw data and (ideally) also know why you made that modification. Dofiles help doing all of this! Why are they called Dofiles? because their extension is .do. Dofiles allow you to quickly reproduce your work and leave comments between your lines of code, so that you can note down what you are doing, and why you are doing it. Ideally a Dofile should be written in a way that allows another Stata user (or your future self, which 99% of the time will NOT remember why you did what you did) to understand everything you did in there without effort.

Guidelines to write dofiles

- Always put clear comment on anything you are doing. The comments should be concise and explain what are you doing and why you are doing it.

- Always put a preamble at the beginning of the dofile explaining what you are accomplishing with that specific dofile.

- Do not put everything inside the same dofile! Try to create one dofile for each task (es. one dofile that cleans the data and another one that analyzes them)

- Automate everything that can be easily automated. (e.g. if you are performing repetitive actions in a dofile you may want to consider using loops to make your code more efficient.

- Avoid hard coding at all costs: DO NOT embed in your code something that cannot be changed directly/is specific to that dataset. Try to use macros and e() or r() results to avoid typing dofiles that will depend on a specific numbers you would always be boudn to check. For more info see: Create a setting for collaborative coding.

- Delete anything that is not essential: I know it feels bad to delete chunks of code you have been working on for hours. However, if you leave them in the middle of your document, they will clutter the space and you are going to start hating them as well. If you are too attached to your old code to delete it, put it at the end of the dofile and use the command

exitso that the dofile stops before reading it. Example

*- END DOFILE --------------------

exit

/*

Old code for task X

put your old code here

Create a folder structure

You should create a folder structure on your laptop where you store all the document and data of the project so that you immediately know where they are. This is important so that you don’t waste time in the future looking for “that dataset I created a wile ago”. The minimum structure I suggest is presented below:

- Data here you store all the data you need for your analysis

- Raw here you store all the raw data (not processed, saved as they come in from the server)

- Processed here you store all the data you manipulated (partial datasets etc.)

- Final here you store all the FINAL data (this should be the final version of the data ready for publication)

- Codes and documentation here you store all your dofiles, R script, documentation of the datasets etc.

- Output here you store all your dofiles, R script etc.

- Tables here you store all the tables that come out as an output from your codes

- Graphs here you store all the graphs that come out as an output from your codes

N.B. You may want to check iefolder, a user-written command the World Bank created to automatically create a folder structure from Stata.

Create a workflow

Create a setting for collaborative coding: Main.do

Being organized is important if you are working on a project on your own. It is much more important so when you are working with other people. Your team most likely will store the project files (Data, codes etc.) on a cloud system (Dropbox, OneDrive, GoogleDrive etc.). Every member of the team should be able to run the scripts from their personal laptop, this means:

- Every person working on the project would need to have the same Stata settings.

- Any eventual command present in other dofiles that is not installed in Stata by default should be installed by everybody.

- Every person should be able to access the data and output folder to reproduce the results.

This information should be ideally contained in a Main.do dofile, that defines the common settings, installs extra command if needed, and provides users direct access to files. 1,2 are easier to achieve, but what about 3? There is a very simple way also to achieve this in Stata, to see it let’s take a step back and explore what are macros in Stata.

Macros (globals and locals)

A common definition for macros is the following1

Macros are abbreviations for a string of characters or a number.

It might not seem so at the moment, but macros are very powerful tools we will use throughout this course. The two macros we will describe now are local and global.

First of all, let’s see which description Stata offers for them:

global assigns strings to specified global macro names (mnames). local assigns strings to local macro names (lclnames). Both double quotes (“ and “) and compound double quotes (‘” and “’) are allowed

This might look very obscure to you, but I promise it will be clear in a moment.

At this stage I would like to think about macros an empty box, where you can store content. You can store pretty much anything you want in that box, either numbers or letters.

local are macros that are valid only as long as you execute commands in do-files.

globals are macros that are valid for the entire duration of the Stata session (so they are valid until you cancel them or you close Stata). A Stata session lasts from the moment you open Stata to the moment you close it. Meaning if you load another dataset without having closed Stata previously, you are in the same Stata session.

Let’s look at the syntax for local

local localname "string" This allows you to store strings

local localname = expression This allows you to store numbers

Example 1: Create your first local

I want to create a local that stores my name, so that when I “call” it or execute it, it will return my name:

local my_name "Gaia Gaudenzi"

display "`my_name'"

Try to copy this code in a dofile, replace it with your name and run the code. What happens? What happens if you run the lines separately?

Example 2: Create your first global

Similarly as we did before, I will create a global that stores my cat name (Minou), so that when I “call” it or execute it, it will return my cat’s name:

global my_cat_name "Minou"

display "$my_cat_name"

Note that I “called” globals and locals in a different way. To show what’s inside a local, you have to put `’ around the name of the local, while to “call” a global you have to put a $ at the beginning of the name of the global.

Try to copy this code in a dofile, replace it with your name and run the code. What happens? What happens if you run the lines separately?

Tips for code: When you are not sure whether you specified a global correctly, just run

display "$nameofglobal"and inspect what is the actual output Stata gives back for that specific global.

Ok. great. But how is this useful? Since globals store strings, we can use them to store directories so that we don’t have to type always the entire directory of a file when we import/export it. This reduces errors and forces you to organize files in “bins” that can be accessed through pre defined globals.

Application 1: Create your first global that stores directory

Tip for code: never use backslashes in your code, these cannot be read by MacOS or Linux laptop

Let’s say I have a Data folder where I store all my data, and I want to import an Excel (called SampleExcel.xlsx) from that folder. The directory of that folder on my laptop is

“/Users/gaiagaudenzi/Documents/Stata/Data”

Note that this directory is specific to my laptop, i.e. it specifically indicates the location of the Data folder on my laptop.

If I want to import SampleExcel.xlsx into Stata, I would have to write:

import excel using "/Users/gaiagaudenzi/Documents/Stata/Data/SampleExcel.xlsx"

However, this is inconvenient for two reasons:

- It is unnecessarily cumbersome: Everytime I would want to refer to this file in the code to import/export it, I would have to attach to SampleExcel.xlsx the whole directory, or run an additional line telling Stata to pick the file from that specific directory like in the example below:

cd "/Users/gaiagaudenzi/Documents/Stata/Data/"

use "SampleExcel.xlsx"

- This “ties” Stata to a directory on my specific laptop. This is not great for collaborative coding since another user that have access to the same file cannot run the dofile automatically.

The solution to this involves the use of macros. We can construct a dofile that stores our specific directories into a macro so that Stata dynamically changes the directory based on the user. (I also recommend doing that even if you are working on a project on your own, because it forces you to follow a structure to catalogue your files so that you never have doubts on where things are).

Pause for thought: Which one of the macro we have seen so far would be adequate for this specific task? global or local? Why?

We can construct a program that tells Stata “If the username of this laptop is X, then the directory from which you have to take the file is Y”. In my case this sentence translates into “If the username of this laptop is gaiagaudenzi, then the directory from which you have to take the file is “/Users/gaiagaudenzi/Documents/Stata/Data/” “

Constructing this program involves 2 steps:

display "`c(username)'"

- Create specific globals that contains the chunk of directory you need to get to your files.

Here below an example of a dofile that creates specific globals for each user so that it allows different people working from different laptops to collaborate on the same file.

* Run this to find your username

display "`c(username)'"

if "`c(username)'"== "gaiagaudenzi" { // Gaia

global directory_root "/Users/gaiagaudenzi/Documents/Stata/Data/"

If you want to add more users, you just add another condition on the if

* Run this to find your username

display "`c(username)'"

if "`c(username)'"== "gaiagaudenzi" { // Gaia

global directory_root "/Users/gaiagaudenzi/Documents/Stata/Data/"

if "`c(username)'"== "otheruser" { // Other user

global directory_root "/Users/otheruser/Documents/Stata/Data/"

Now, try to run

display "$directory_root"

Pause for thought: If the setting of the global is correct, what should be the output of this line of code?

From this point you can:

- map your folder structure into this dofile to create globals that access all the folders

- directly create the folder structure from here

Code for option 1:

Before creating this dofile, I manually create the folder into my project folder, and then I construct the globals to accesss to it.

* Run this to find your username

display "`c(username)'"

* Create the global root

if "`c(username)'"== "gaiagaudenzi" { // Gaia

global directory_root "/Users/gaiagaudenzi/Documents/Stata/"

if "`c(username)'"== "otheruser" { // Other user

global directory_root "/Users/otheruser/Documents/Stata/"

* Define globals to access all folders in the project (use directory_root)

global data "$directory_root/Data"

global output "$directory_root/Output"

* Specific output globals

global tables "$directory_root/Output/Tables"

global graphs "$directory_root/Output/Graphs"

Pause for thought: What did I do here? I used the previously created global ($directory_root) to create another global. Why is this important? How do I make sure globals work?

Option 1: Comment the mkdir section (recommended)

/*

mkdir "$directory_root/Data"

mkdir "$directory_root/Output"

* Specific output globals

mkdir "$directory_root/Output/Tables"

mkdir "$directory_root/Output/Graphs"

*/

Option 2: use capture. You can use it in front of every command. It tells Stata to basically ignore the error and continue running the dofile if it encounters an error on that specific line. It is not advisable in general to use capture because if there is an error, then it means that something with your data is wrong. In this case we know the source of error, so we actually don’t care that Stata keeps running even in the presence of one error. In other cases, it might be relevant to know why Stata stopped working and what kind of error it ecountered.

capture mkdir "$directory_root/Data"

capture mkdir "$directory_root/Output"

* Specific output globals

capture mkdir "$directory_root/Output/Tables"

capture mkdir "$directory_root/Output/Graphs"

The World Bank has created iefolder, a very nice command to create standardized folder structures, you may want to check it out!

So now we can have a look at how a Main.do should look like. As we said previously it should:

- Set the basic Stata settings.

- Install any extra commands.

- Provide dynamic user-specific paths.

* 1. Set Stata settings

clear all

clear matrix

clear mata

clear results

set more off

set maxvar 20000

capture log close

* 2. Install extra commands

ssc install tabmiss

ssc install dropmiss

* 3. User-specific paths

* If you forgot your username run:

display "`c(username)'"

if "`c(username)'"== "gaiagaudenzi" { // Gaia

global directory_root "/Users/gaiagaudenzi/Documents/Stata/"

if "`c(username)'"== "otheruser" { // Other user

global directory_root "/Users/otheruser/Documents/Stata/"

* Define globals to access all folders in the project

global data "$directory_root/Data"

global output "$directory_root/Output"

* Specific output globals

global tables "$directory_root/Output/Tables"

global graphs "$directory_root/Output/Graphs"

Data cleaning

Explore your data

codebook

summarize

tab

describe

isid

assert

inspect

compare

list

destring/tostring

As we saw before, Stata has different formats for variables (mainly numeric, string and labeled). If you are trying to perform a command on a numeric variable that has been imported as string, you get an error. Luckily, you can convert a string variable into a numeric one using destring .

To convert a numeric variable into string you can use destring :

* To convert a string variable into a numeric variable

destring(var), replace

* To convert a numeric variable into a string variable

tostring(var), replace

* To convert ALL variables in the dataset into numeric

destring(*), replace

N.B. If a variable contains string characters other than plain numbers, Stata will NOT convert the variable into a numeric one. Check the output of your destring/tostring to understand if Stata performed it correctly.

N.B. In general, I prefer to import all variables as string, so that I can inspect them as they are (check the date format etc.) and then destring what I need.

Identify missing values

There might be different types of missing values. If you are running a survey, then a value might be missing for a specific question because the person didn’t know the answer, because he/she refused to answer or other reasons. It is important to distinguish between these different types of missing values so that you can make further considerations on your study design or implementation (i.e. was the question too hard? Is the question posed in a way that might make respondents feel threatened? etc.)

The code to identify/categorize missing values on Stata is mvdecode.

Let’s say you ran a survey, and for question 1 (we will refer to it as Q1) you have these values:

Q1 Do you like school? 1= Not at all 2= A little 3= I like it 4= I love it -96= I don’t know -99= I don’t want to answer

How do you categorize the values that have been recorded as missing (namely -96 and -99) ?

* Decode missing values (Use .d for "Don't know'" and .r for "Refuses to answer")

mvdecode Q1, mv(-99=.d \ -96=.r)

This will change the numeric values from numeric to missing values (and will preserve the reason why they are missing values)

Note: Stata categorized missing values as “infinity”. You should keep this in mind every time you type specific codes for which the result might change e.g. gen var_new if var > 10000 This will also include missing values.

Dealing with duplicates

Another challenge when working with data will be to identify potential duplicates. To do that you have first to identify what is the unique identifier of your dataset (or your id). By looking at the data you should be able to identify it. To check whether a variable (or a combination of them) is an id, type:

isid id_name

This will tell you if a variable is a unique identifier of the observations. If not, you should look at how many duplicates does the data have. To flag duplicates, run:

* Flag duplicates

duplicates tag id_name, gen(tag)

* Tab the result of flagging duplicates

tab tag

Then you’ll have to inspect manually the duplicates to see if they really are duplicates or if there is another mistake in the data.

Renaming variables

The syntax for renaming variables is really simple, you just have to run:

rename oldvar newvar

But what about renaming a group of variables? Let’s say I want to rename a set of variables with the same prefix because I want to signal that these variables come from the same dataset D1 :

renvars _all, prefix(D1_)

renvars might come handy also when you want to reshape a dataset from wide to long format. See the reshape section for more details.

Labeling variables

It is important to have a clean dataset with all the variables (and the values inside them) correctly labeled. This will avid confusion when you are running your analysis. To label variables:

label var varname "Variable Label"

To label values inside a variable:

* First step: define the value labels

label define yesno 1 "Yes" 0 "No"

* Second step: Attach value labels to values

label values var yesno

Renaming and labeling values might be a boring and repetitive job. Especially when there is no automated way to do that and you have to rename everything from scratch. Here there is a tool that might come handy if you have to rename an entire dataset in a non-uniform way (i.e. you actually need to change the name of the variables, not just adding prefixes/suffixes). This file is an Excel file that automates a little bit the process of renaming by using the concatenate function in Excel. It then produces a code you can easily copy and paste into Stata for renaming/labeling a buch of variables.

A note on generating variables:

egen vs gen

What is the difference between egen and gen?

In theory, there is no significant difference, they both generate new variables. However, they work with different functions.

The story on why egen and gen exist is not entirely clear to some people, more information here

Let’s look at the Stata documentation helpfile:

generate [type] newvar[:lblname] =exp [if] [in] [, before(varname) |

after(varname)]

egen [type] newvar = fcn(arguments) [if] [in] [, options]

In practice, we care about this distinction only to know whether with a specific function we should use egen or gen. For example the functions mean(), sum(), total(), rowtotal() work only with egen.

WARNING: Sometimes a variable can be generated both by egen and gen, but it can give very different outputs. For example, summing variables in gen will preserve missing values, while summing a variable using rowtotal() in egen will turn missing values into 0. Depending on where you want to use this new variable for, you should be extra careful about how your missing data are handled.

bysort + _n vs _N

What are _n and _N? They are built-in variables in Stata.

- _n gives you the number of the specific observation you are looking at (whether it is the first, the second etc.)

- _N gives you the total count of the observations in the datasets (i.e. _N=500 if you have 500 observations in the dataset) To make sure you understand what they do, create these 2 new variables:

gen obsnum = _n

gen totnum = _N

Nice to know, but not very useful so far. However, they become pretty powerful when used in combination with by or bysort(). For example, if you have panel data, and you want to know how many observations are in the dataset for a single person:

bys id year: g num_obs_per_person=_n

calling results from r() and e()

Sometimes you want to create a variable based on the summary statistics of another variable. For example, you may want to create a dummy = 1 if the total score of something is below the average. Normally, you would summarize the variable that contains the total score, then you will pick from there the average value to generate your dummy. You should NOT HARD CODE THE VALUE OF THE AVERAGE, i.e. looking at the value of the average and hard code it into the dofile. There is a better and more automated way to achieve that!

Some commands store results in their memories. For example, if you run summarize and then return list you will see something like this:

XXX

This ensures that Stata will always have the correct number of the average, even if we change the input dataset to load a more updated one.

gen below_average=totalscore<`r(mean)'

Cleaning strings

Sometimes you may want to insert something in your analysis that is contained in the string variable, but in order to use them you have to ensure they are clean. Stata is case sensitive so the string “Stata” is different to the string “stata”. Luckily, there is a farly easy way to homogenize variables. How to use them? They are not properly commands, but functions, so you cannot type directly the function on Stata, you would need an “auxiliary” command. Examples below:

trim Removes all the excess spaces outside a string variable

itrim Removes all the excess spaces inside a string variable

proper converts all the first letters of a string in uppercase. (e.s. gaia gaudenzi becomes Gaia Gaudenzi). Might be useful as a starting point to clean names.

lower converts the entire characters of the strings in lowercase.

upper converts the entire characters of the strings in uppercase.

* Remove excess spaces outside variable

replace var=trim(var)

* Remove excess spaces inside variable

replace var=itrim(var)

* You can also combine them to remove excess spaces outside or inside

replace var=trim(itrim(var))

* Capitalize Each Letter

replace var=proper(var)

* all lowercase

replace var=lower(var)

* ALL UPPERCASE

replace var=upper(var)

Other string functions

split splits the contents of a string variable creating new string variables.

substr returns the substring of a string, starting from where you like.

subinstr replaces part of a string with another string.

strpos returns the position at which a piece of string is found.

length returns the length of a string

regexm looks at a string to find a specific substring and returns the value of 1 if there is a match.

N.B. Remember that these functions are all case sensitive!

* SPLIT

split date, parse("-")

rename date1 year

rename date2 month

rename date3 day

* SUBSTR

/*

substr(s,n1,n2)

Description: the substring of s, starting at n1, for a length of n2

*/

g name = substr(project,strpos(project,"-")+2,.)

* SUBINSTR

/*

subinstr(s1,s2,s3,n)

Description: s1, where the first n occurrences in s1 of s2 have been replaced with

s3

*/

* remove dots

replace task=subinstr(task,".","",.)

* STRPOS

/*

strpos(s1,s2)

the position in s1 at which s2 is first found, 0 if s2 does not occur, and 1 if s2 is empty

*/

g has_var=strpos(task,"var")

* LENGTH

* REGEXM

/*

regexm(s,re)

Description: performs a match of a regular expression and evaluates to 1 if regular

expression re is satisfied by the ASCII string s; otherwise, 0

*/

* Task cleaning with regexm

ta task, m

g has_var=regexm(var,"[Vv]ar")

Little dictionary on Stata Regular expressions useful to handle string variables

Counting

*Asterisk means “match zero or more” of the preceding expression.

+Plus sign means “match one or more” of the preceding expression.

?Question mark means “match either zero or one” of the preceding expression.Characters

a–zThe dash operator means “match a range of characters or numbers”. The “a” and “z” are merely an example. It could also be 0–9, 5–8, F–M, etc.

.Period means “match any character”.

/A backslash is used as an escape character to match characters that would otherwise be interpreted as a regular-expression operator.Anchors

^When placed at the beginning of a regular expression, the caret means “match expression at beginning of string”. This character can be thought of as an “anchor” character since it does not directly match a character, only the location of the match.

$When the dollar sign is placed at the end of a regular expression, it means “match expression at end of string”. This is the other anchor character. Groups|The pipe character signifies a logical “or” that is often used in character sets (see square brackets below).

[ ]Square brackets denote a set of allowable characters/expressions to use in matching, such as [a-zA-Z0-9] for all alphanumeric characters.

( )Parentheses must match and denote a subexpression group.

Extended functions

-

Use a local that displays a progressive number

local i=1

forvalues x=0/5 { // or firstvalue(intervalnumber)lastvalue

display

x' displayi’local ++i

}

Working with dates

Data processing

Reshape

You can reshape in long or wide form. To perform the majority of analyses with STATA you will need 99.9% of the time a reshape long, while usually a reshape wide is useful to make more readable the tables you export. You can reshape according to a string or numerical variable. The syntax is the following:

Where stub can be

- a single variable: stub

- All variables that start with the same prefix: stub*

-

An interval of variables: stubfirstvar-stublastvar

i(i) is your ID variable j(j) is the variable whose unique values denote a subobservation (usually is the year)

Randomization

When you are drawing a random subset of a sample, to make it reproducible, you have to make sure you set the seed first, before you actually draw the sample to do that type:

set seed 87

To sample 10% of the sample

sample 10

To sample 200 observations in the sample

sample 200, count

Automation: Loops

sysuse auto

* To loop over a set of strings

foreach x in trunk weight length {

display "`x'"

}

* To loop over a set of numbers

forvalues x=1/5 { // or firstvalue(intervalnumber)lastvalue

display `x'

}

* To loop over a set of variables

foreach var of varlist price-gear_ratio { // or firstvalue(intervalnumber)lastvalue

display "`var'"

}

* To loop over a set of values of a variable

levelsof make, local(maker)

foreach m in `maker' {

di "`m'"

}

Data exporting

Data visualization

Graphs in a nutshell

Graphs with error bar

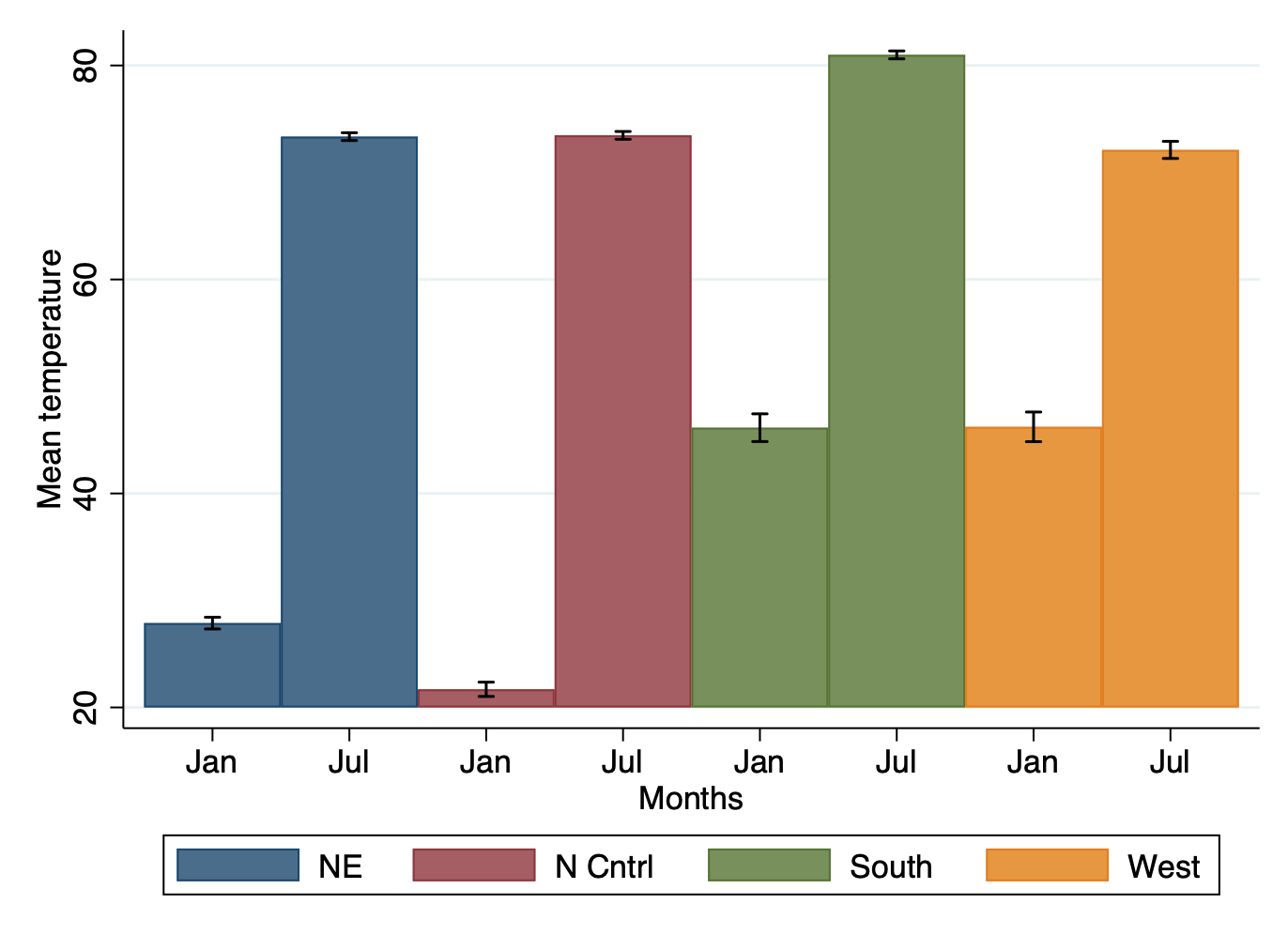

Creating a graph with error bar in Stata involves some transformation of the dataset. If you are not familiar with collapse or reshape, please visit the corresponding section. Here we would like to create a graph with the corresponding error bars. Let’s use the built-in dataset city temp.dta`

to show how to build a graph with error bar.

* Load data

sysuse citytemp.dta

We see that the dataset records different temperatures in two times of the year: January and July. We would like to create a bar graph that shows the average temperatures in the 2 months by region, but also showing confidence intervals. We start forming our dataset to create the graph:

collapse (mean) mean_tempjan=tempjan mean_tempjul=tempjul ///

(sd) sd_tempjan=tempjan sd_tempjul=tempjul ///

(count) n_tempjan=tempjan n_tempjul=tempjul, by(region)

reshape long mean_temp sd_temp n_temp, i(region) j(month) str

Then, we calculate upper and lower values of confidence intervals

generate hi_temp = mean_temp + invttail(n-1,0.025)*(sd_temp / sqrt(n_temp))

generate lower_temp = mean_temp - invttail(n-1,0.025)*(sd_temp / sqrt(n_temp))

Now we generate a “fake” x-axis, which will allow us to plot the bars exactly in the order we want

generate xaxis = 1 if region == 1 & month == "jan"

replace xaxis = 2 if region == 1 & month == "jul"

replace xaxis = 3 if region == 2 & month == "jan"

replace xaxis = 4 if region == 2 & month == "jul"

replace xaxis = 5 if region == 3 & month == "jan"

replace xaxis = 6 if region == 3 & month == "jul"

replace xaxis = 7 if region == 4 & month == "jan"

replace xaxis = 8 if region == 4 & month == "jul"

And we are ready to generate the graph:

twoway (bar mean_temp xaxis if region == 1) ///

(bar mean_temp xaxis if region == 2) ///

(bar mean_temp xaxis if region == 3) ///

(bar mean_temp xaxis if region == 4) ///

(rcap hi_temp lowr_temp xaxis, color(black)), ///

legend(row(1) order(1 "NE" 2 "N Cntrl" 3 "South" 4 "West") ) ///

xlabel( 1 "Jan" 2 "Jul" 3 "Jan" 4 "Jul" 5 "Jan" 6 "Jul" 7 "Jan" 8 "Jul") ///

graphregion(color(white)) ///

xtitle("Months") ytitle("Mean temperature")

Maps

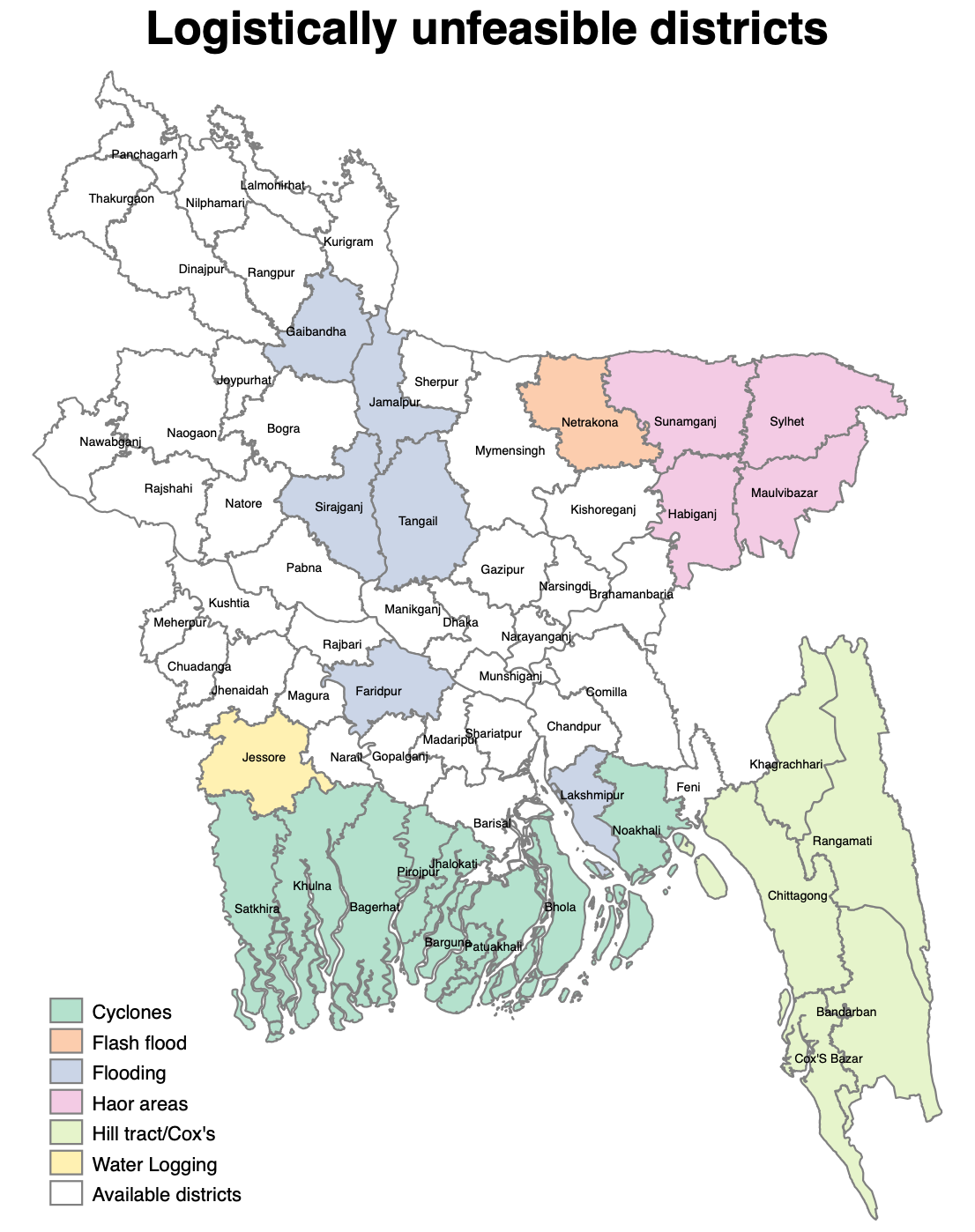

Did you know you can create simple maps in Stata? This is thanks to the absolutely awesome people that invented the spmap command. Here below the code to create this simple map of Bangladesh. I created this map when I was in Bangladesh right before a data collection, to visually see in which districts it was impossible to go during the monsoon season in that specific year.

The first thing you need to do, is to download a shapefile with the administrative division that interests you (just google Country X shapefile and download). You will need to have a file with the extension .shp, which you can convert in .dta and exploit for graphs. Let’s see all the steps below:

* 1 STEP: Convert shapefile to .dta

shp2dta using ///

"$maps/gadm36_BGD_2.shp", ///

data("$maps/BGD_zilamap") ///

coor("$maps/BGD_zilacoor") ///

replace genid(id)

u "$maps/BGD_zilamap.dta", clear

spmap using "$maps/BGD_zilacoor.dta", id(id)

* Mark unfeasible districts

u "$maps/BGD_zilamap.dta", clear

* 1.1 Mark Hill tract areas

#delim ;

g var = "Hill tract/Cox's"

if NAME_2 == "Chittagong"

| NAME_2 == "Khagrachhari"

| NAME_2 == "Rangamati"

| NAME_2 == "Bandarban"

| NAME_2 == "Cox'S Bazar"

;

#delim cr

* 1.2 Mark Haor areas

#delim ;

replace var = "Haor areas"

if NAME_2 == "Sylhet"

| NAME_2 == "Maulvibazar"

| NAME_2 == "Habiganj"

| NAME_2 == "Sunamganj"

;

#delim cr

* 1.3 Mark areas affected by Cyclones

#delim ;

replace var = "Cyclones"

if NAME_2 == "Khulna"

| NAME_2 == "Bagerhat"

| NAME_2 == "Pirojpur"

| NAME_2 == "Jhalokati"

| NAME_2 == "Patuakhali"

| NAME_2 == "Barguna"

| NAME_2 == "Bhola"

| NAME_2 == "Noakhali"

| NAME_2 == "Satkhira"

;

#delim cr

* 1.4 Mark areas affected by flooding

#delim ;

replace var = "Flooding"

if NAME_2 == "Faridpur"

| NAME_2 == "Sirajganj"

| NAME_2 == "Tangail"

| NAME_2 == "Jamalpur"

| NAME_2 == "Gaibandha"

| NAME_2 == "Lakshmipur"

;

#delim cr

* 1.5 Mark areas affected by water logging

replace var = "Water Logging" if NAME_2 == "Jessore"

* 1.6 Mark areas affected by flash flood (if not already eliminated)

replace var = "Flash flood" if NAME_2 == "Netrakona"

encode var, g(var2)

preserve

* Create labels (not compulsory)

u "$training_data/4_Data visualization/Map/BGD_zilacoor.dta", clear

collapse (mean) _X _Y, by(_ID)

rename _ID id

merge 1:1 id using "$maps/BGD_zilamap.dta"

keep id _X _Y NAME_2

save "$training_data/4_Data visualization/Map/BGD_label_coor", replace

restore

* 1.7 Create map

spmap var2 using "$maps/BGD_zilacoor.dta" , ///

id(id) clmethod(unique) ocolor(gs8 ..) fcolor(Pastel2) ndocolor(gs8 ..) ///

name(base, replace) ndlab("Available districts") ///

title({bf:Logistically unfeasible districts}) ///

label(data("$maps/BGD_label_coor.dta") ///

label(NAME_2) xcoord(_X) ycoord(_Y) length(20) size(*0.5) gap(*1) color(black)) legend(pos(7))

graph export "$training_output/Bangladesh_map.png", as(png) replace

Great resources to learn Stata online

There is only one way to get proficient with Stata: to have PATIENCE. Practice is fundamental to become better and better, do not get discouraged if you are not able to achieve what you want at the beginning. Stata prizes people who have patience and practice with perseverance. Hopefully this training and my source code will help you navigating the immense world for Data Cleaning, Processing and Analysis with Stata and will make the whole learning path easier and funnier! In the meantime, I leave you with some sources to learn Stata online that were extremely useful for me:

- Stata official website

- UCLA website

- Princeton Stata tutorial

- Stata web books from UCLA

- Code and Data

- Getting Started in Data Analysis using Stata

- Stata Tutorial

- Stata Basic

- Getting Started with Stata, Princeton University

- Julian Reif’s website

- Alvaro Carril’s website

- Stefania Lovo’s website

- Alex Bhatt’s manual

Data analysis

References

Appendix: List of commands

-

Long, J. Scott. 2009. The Workflow of Data Analysis Using Stata. College Station, TX: Stata Press. ↩